Before sailors etched their routes in salt or kingdoms cast their gaze across the waves, the Earth was already shaping the Seto Inland Sea. It began over three million years ago, when the vast force of the Median Tectonic Line, Japan’s longest and most restless fault, heaved the land into motion. Mountains rose on either side of what would one day become a sanctuary for mariners, poets, and empires. The basin that stretched between the Chūgoku and Shikoku ranges remained caught in a state of restless transition, carved by tectonic pressure, fractured by volcanic eruptions, lifted and reshaped over eons. This was not a gentle process. The land burned, split, and folded in on itself, rewriting its own map through fire and upheaval.

For a time, the basin lay bare. During the last great ice age, sea levels dropped and the ocean withdrew, leaving behind an arid plain scattered with the bones of ancient stone. But as the planet warmed and the glaciers melted, the water returned. Slowly, it crept back into the land’s hollows, flooding valleys, submerging ridges and curling around rising peaks. What remained was an inland sea, quiet, protected, and unlike any other in the world. More than 3,000 islands surfaced from the flood, each with its own contours and character, scattered across the calm water like stepping stones between three great islands. The sea had found its form. Its silence became a mirror. Its channels, a network of pathways for those who knew how to read them.

It was here, amid this complex, sheltered seascape, that a distinct maritime culture began to emerge. Long before modern borders were drawn, these waters belonged to the sailors.

Merchant ships and fishing vessels sailed from cove to cove, bearing salt, silk, and ceramics. Port towns flourished along narrow shorelines, their harbors alive with the sound of wooden hulls and shouted deals. Shrines stood watch on the hills above, their vermilion gates facing the tides. There were pirates, too, clever navigators who vanished into the maze of islands with their spoils. For centuries, the Seto Inland Sea moved in rhythm with the ambitions of the people who sailed her. She offered protection, but demanded skill.

Then the world began to close in. As foreign ships arrived on distant coasts, Japan turned inward. In the early 1600s, under the Tokugawa shogunate, the country entered a period of enforced isolation. The Setouchi, once open to outside winds, became a sealed theatre. Foreign vessels were forbidden to approach. Trade was tightly controlled. The islands settled into a slower rhythm, guided not by the currents of empire but by the cycles of tide, harvest, and prayer. In this long silence, a culture emerged that was neither frozen nor forgotten, but carefully maintained. Villages held their shapes. Languages retained their cadences. The past remained present.

When I arrived, I came with curious eyes. I expected quiet beauty, perhaps a sense of distance from the pulse of modern Japan. But what I found along these shores was something else, something deeper. The sea here speaks, softly but with clarity, if one is willing to listen. It tells of fire and water, of centuries-old crossings and rituals still unfolding. Setouchi holds her history not behind glass, but in the grain of her boats, in the scent of her kitchens, in the curve of her islands seen from the water’s edge.

A City Reborn in Reflection and Ritual

Arrival in Japan is never a casual moment. The descent, the final glide over a coastline laced with islands and mountainous silhouettes, marks the beginning of a journey that often unfolds inwards as much as outwards. My passage into the Setouchi region began in Hiroshima, a city whose name carries the weight of history, yet whose presence today speaks of resilience, grace, and extraordinary renewal. It is the largest city in the region, a cultural and industrial center that has risen from ashes with quiet dignity and an unwavering sense of identity.

The Hilton Hiroshima received us with effortless poise, offering exactly what one hopes for after a long transoceanic flight: composure, comfort, and the kind of hospitality that anticipates rather than responds. Nestled in the city center, the hotel places you within minutes of Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park, Hiroshima Castle, and the lively Hondori district. From the windows of the room, the city stretched toward the mountains, its skyline reflecting both ambition and intimacy. At night, the lights shimmered with the calm assurance of a place that has seen everything, and learned to cherish every moment.

Hiroshima’s streets, modern and efficient, pulse with a kind of quiet energy. Here, among sleek buildings and clean boulevards, the past is never far. You walk a block and find a shrine pressed gently between concrete and glass. At Shirakami-sha Shrine, I paused beside an old stone gate, where early morning light filtered through trees onto gravel paths. Commuters in suits bowed their heads with the same reverence as students in uniform. A sign explained that this site, once submerged by sea, had long been sacred; a reef marked by white paper flames to guide sailors, now enshrined as Shirakami, the “White God.” The language of the shrine spoke softly but clearly: here, the divine and the ordinary live side by side.

Shrine culture in Japan, rooted in Shintoism, is not ornamental. It is a daily rhythm, a thread woven through the fabric of life. Whether offering a coin, a bow, or a whispered wish, there is a shared understanding that one is stepping into the presence of the kami, the spirits that dwell in sacred objects, ancient trees, even the sea itself. In this way, every shrine becomes a vessel of continuity, and every visit a quiet act of preservation.

There is no way to approach Hiroshima without acknowledging her most searing memory. The Peace Memorial Park stands as a promise etched into stone, suspended in silence, and surrounded by thousands of paper cranes folded by children who will never know the violence firsthand. It is a place of gravity, but also of clarity. The message is unspoken, yet understood: this must never happen again. The experience is not heavy. It is precise. It holds you still, and then lets you move forward with deeper awareness.

Yet for all this solemnity, the city surprises constantly. A tiny café selling exquisite ceramics found nowhere else. A bookstore with shelves of handwritten notes tucked between the pages. A stand grilling okonomiyaki in the local style, where layers of cabbage, pork, noodles and batter are pressed into something both hearty and exacting. There is always something just around the corner that catches the eye and pulls you toward it.

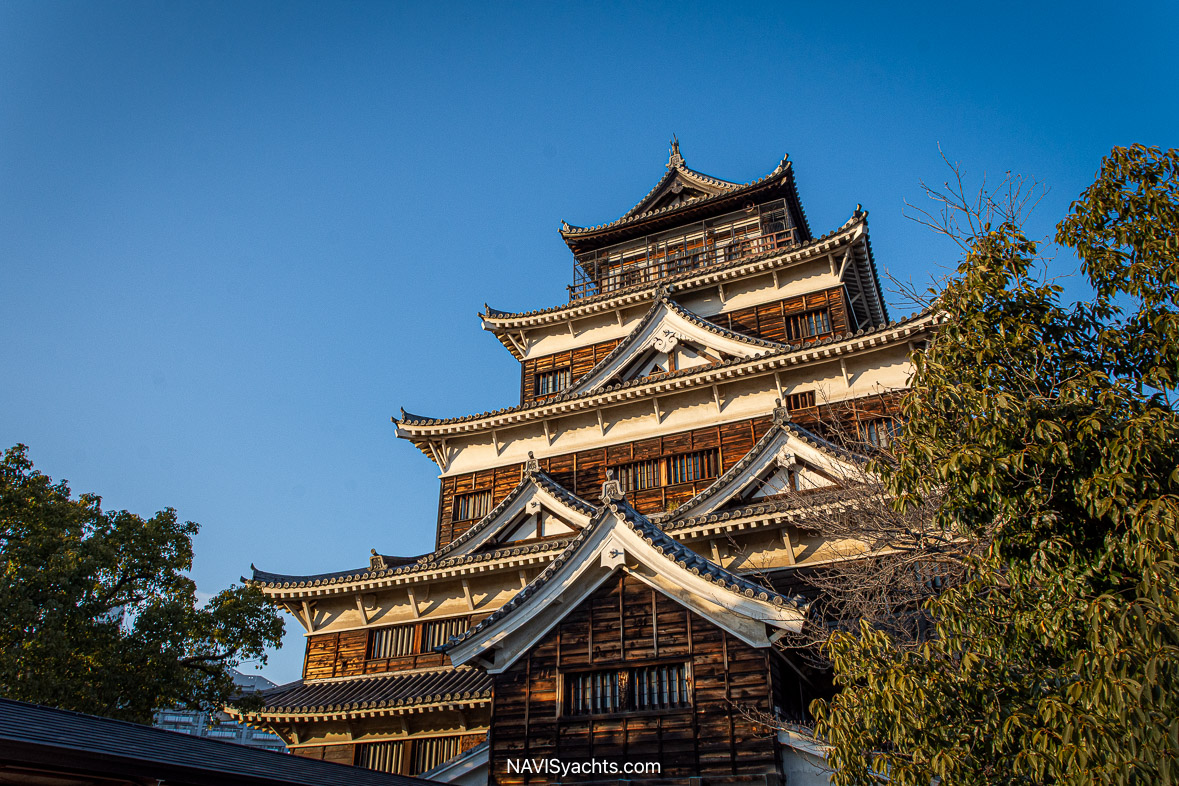

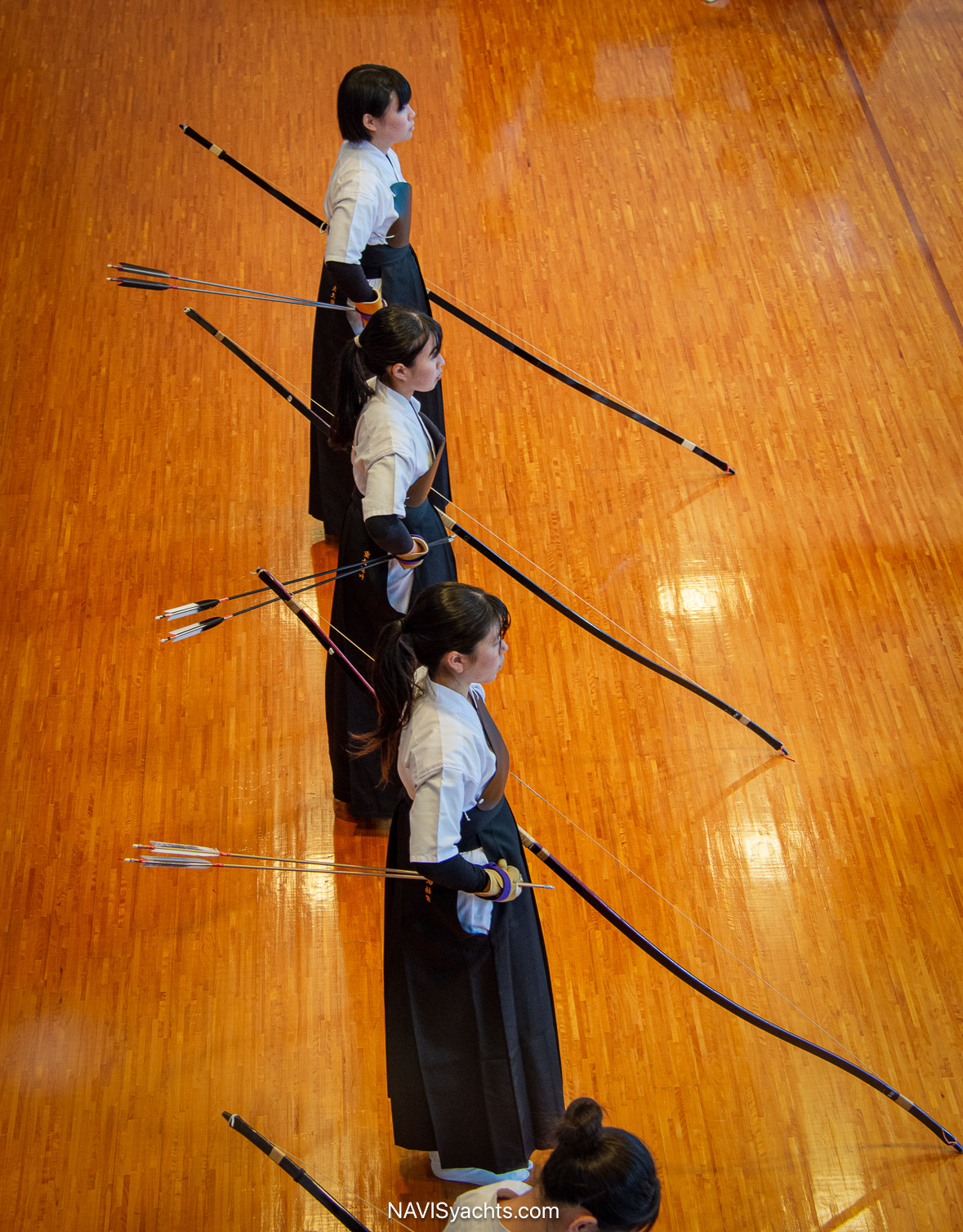

At Hiroshima Castle, rebuilt with faithful detail after its destruction in 1945, I walked through carefully curated gardens and stood beneath ancient-style eaves, imagining the feudal lords who once ruled from these heights. Nearby, beneath a sharp blue sky, a group of school children were practicing kyūdō, Japanese archery. Dressed in traditional uniforms, their forms were precise, movements quiet and assured. Kyūdō is a spiritual discipline, a pursuit of stillness within motion, grace under tension. It is less about the target and more about the moment of release.

That evening, we had the opportunity to meet Mr. Hiroshi Sakamoto, Managing Director of the Setouchi Tourism Authority, who invited us to experience a traditional Kagura performance, an unexpected immersion into the ceremonial heart of Japanese folklore. That night’s play, Tsuchigumo (The Demon Spider), was performed by the Yoshida Kagura troupe with astonishing vitality. Elaborate hand-embroidered costumes shimmered under the stage lights, some weighing more than 20 kilograms, while musicians played taiko drums and flutes entirely by ear, their rhythms passed down orally for generations. Kagura originated as a ritual to honor the gods and celebrate the bounty of nature. The spectacle was ancient and electric, a vivid reminder that the spiritual traditions of this region are still lived.

Hiroshima was the beginning of this journey, and the perfect threshold into the cultural richness of southern Japan. The city’s rhythm is steady and composed, welcoming without spectacle.

Here, I found a place where modern life and centuries-old tradition hold each other in respectful balance. It is a place that invites you to slow down, to observe, and to begin listening more carefully to the people, to the land, the sea, and the long memory they share.

Miyajima: The Island Where the Gods Reside

There are places on Earth where nature and belief have been interwoven so seamlessly that the landscape itself feels consecrated. Miyajima is such a place. Just off the coast of Hiroshima, the island has long been revered not simply for its beauty, but for its sanctity. It is said that the gods live here, and from the moment one arrives, by rail, ferry, or sea, the feeling is unmistakable. The mountains that rise above the water form, from certain angles, the calm profile of a face. Locals call it the face of good. The entire island is seen as divine. Itsukushima Shrine, the island’s most celebrated structure, was not built on sacred ground, but beside it, upon the tidal shore, in recognition that the land itself is a body worthy of worship.

Itsukushima Shrine traces its origin to the late 6th century. Its current, solemn form is credited to Taira no Kiyomori, the powerful military leader who rose to prominence in the 12th century.

The shrine’s buildings, painted in luminous vermilion, stand on stilts over the sea, their silhouettes changing constantly with the tide. At high water, the entire complex appears to float, tethered delicately to the land by covered walkways. The interplay of elements, the forest behind, the sea in front, the lacquered wood between, forms a tableau that captures the Japanese aesthetic in its purest sense: harmony, reverence, impermanence.

At night, the shrine glows. Subtle lighting reveals the curve of beams and the glint of painted surfaces, casting a gentle radiance across the water. In the quiet hours of morning, the atmosphere shifts again. There is something profoundly moving in watching sunlight creep over the forested hillside, illuminating pagodas and temples in gold and green. Above the shrine, on a slope softened by age, the five-story pagoda stands like a flame of color. Built in 1407 with Chinese-influenced Zen techniques, its lines are both ornate and restrained. Next to it is Senjōkaku, the “Pavilion of a Thousand Tatami,” begun in 1587 under Toyotomi Hideyoshi as a hall for memorial services. Left unfinished after his death, the wooden beams rise into open air, massive and bare, their surfaces still showing touches of gold leaf where the work once progressed.

A short walk westward leads to Daishō-in, one of the most spiritually significant temples in the region. It was founded by Kūkai, the great monk also known as Kōbō Daishi, who completed a hundred days of ascetic training atop nearby Mount Misen in the early 9th century. Daishō-in is a contemplative world unto itself, terraced paths lined with rows of carved Buddhas, moss-covered steps, incense drifting through quiet courtyards. Since ancient times, emperors, generals, and pilgrims have come here in search of wisdom. The sense of continuity is palpable.

Much of Miyajima remains forested and untouched, its slopes protected and preserved as part of a World Heritage Site. The island’s botanical variety is staggering, and its natural rhythm is deeply seasonal, cherry blossoms in spring, flame-colored leaves in autumn, the deep green hush of summer heat. From the base of Mount Misen, one can ascend to the summit, 535 meters above sea level, by foot or by cable car. The climb is a quiet meditation, the trail winding through ancient forest, past wandering deer and trickling streams. At the peak, a cluster of boulders seems to have been dropped from the sky. From the observation platform, the Seto Inland Sea stretches into haze, islands drifting in every direction like painted brushstrokes on blue silk.

The island’s traditions are alive in daily motion. On the main thoroughfare, Omotesandō, visitors gather in shops and cafés, but it takes only a few steps down a side path to find silence and authenticity. Wooden homes lean into narrow lanes. Deer walk beside you, as if expecting to be greeted. At times, I was transported completely—particularly when exploring the island’s historic streets by rickshaw. The sound of wooden wheels turning over stone echoed like a memory, a glimpse into centuries of movement and ritual. The rickshaws themselves are symbols of pride, run by local men who carry their heritage with strength and elegance.

In Miyajima, the sacred is not held apart, it flows into the daily, into the breath and movement of the island. To walk her trails, to pass beneath her torii, is to step into an older rhythm.

Voyaging Through Time on the Seto Sea

The Seto Inland Sea reveals herself not in grand gestures, but in layers. She must be navigated slowly, island by island, moment by moment, like turning the pages of an old, finely illustrated scroll. Over the following days, we left the mainland behind and began to explore her inner sanctum, tracing a line through quiet waters and timeworn ports, uncovering places that have endured precisely because they were never asked to modernize too quickly. M/Y Ocean Point VII, a 23-meter Mochi Craft yacht in pristine condition from JoyCruise charters, carried us through the sheltered waters of Setouchi, her classic lines and measured pace in quiet harmony with the region’s timeless rhythm. The team at Joycruise curated a seamless experience, allowing us to discover towns that feel untouched by the rush of the modern world, where stories linger in the streets and meals carry the weight of centuries.

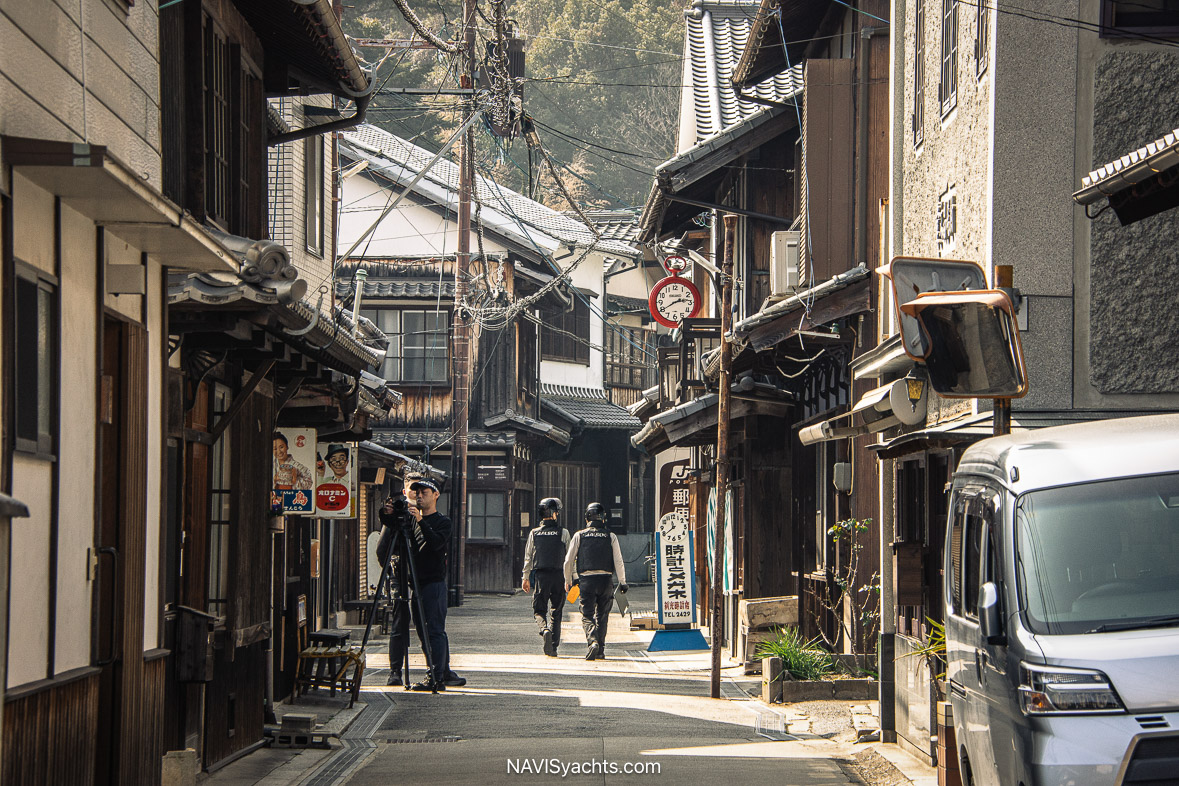

Our first port of call was Mitarai, a small village on Osaki Shimojima Island that once bustled with merchants, sailors, and courtesans, and today stands remarkably intact. Its streets follow the same pattern they did during the Edo period, a quiet grid where wooden facades lean inwards as if still whispering news from the harbor. The architecture is humble and perfect, entirely wooden, elegantly aged, and resolutely human in scale. Near the center of town, we visited a local shrine, modest in structure but powerful in placement, nestled just beside an ancient freshwater well. According to local lore, pirates once docked here to refill their barrels, and the town itself emerged around this essential source.

Inside The Tea Cosy, we met photographer Tom Miyagawa Coulton, whose English was flawless and whose storytelling brought the town to life with vivid clarity. There is something invaluable in hearing the history of a place from someone who both belongs to it and sees it with an artist’s eye. Afterward, we returned to M/Y Ocean Point VII for lunch. The chef on board had prepared a four-course meal of rare quality, delicate oysters, tender fish, seared meats, each dish composed with reverence for Japanese culinary tradition and plated with the precision of a Michelin-starred kitchen. As we sailed between islands, flavors unfolded like stories, each bite a gesture of the region’s generosity.

Later that day, we arrived in Onomichi, a hillside port city with narrow streets, tiled roofs, and the kind of quiet poetry that reveals itself slowly. The famed Temple Walk winds through the hills, past shrines and ancient trees, each turn in the path offering a different vista, a different stillness. Midway through our ascent, we came upon a small tea house, barely marked from the outside, nestled into the slope. We removed our shoes and stepped inside.

Genki Takahashi, the young tea master and owner, greeted us with quiet enthusiasm. His space was a perfect composition of Japanese minimalism, wood, paper, light, and emptiness arranged with purpose. With the harbor spread out below us, he guided us through a tea ritual that felt like a conversation across time. The scent of the leaves, the warmth of the cup, the calm attention in every gesture, this was tea as heritage, as art, as meditation.

That evening, we settled into Ryokan Onomichi Nishiyama, a property that embodies the essence of omotenashi, Japan’s deep, intuitive hospitality. Set above the water, framed by a private garden of over 300 meticulously groomed pine trees, the ryokan offered a sense of privacy and poetry that hotels cannot match. Originally a historic tea garden for wealthy shipowners and merchants, the building has been lovingly restored with materials and objects that trace the lineage of the region: alcove wood repurposed into room keys, old roof tiles transformed into design features. Every corner held a memory.

Dinner was served in the glass-walled restaurant Yosoro, a name drawn from nautical tradition that means “steady,” or more tenderly, “welcome.” The chef prepared each course before us, speaking softly about the ingredients and their origins, scallops paired with canola flower and Mihara blood orange, abalone from Ehime, flounder from local waters, Onomichi wagyu with turnip, and a final note of hazelnut and petit fours. The cuisine felt like a letter from the region, written in taste and texture. Our suite, one of several housed in restored buildings transported to Onomichi by boat, offered complete serenity. Wooden-framed windows opened to views of the inland sea, and the interior balanced tradition and comfort in quiet dialogue.

In the morning, we continued to Kurashiki, arriving in the historical quarter known as Bikan, where Edo- and Meiji-era buildings line the willow-shaded canal. This was once a vibrant center of commerce, and today its white-walled storehouses, stone bridges, and quiet waterways remain impeccably preserved. We stayed in a charming ryokan located directly above the canal, offering views of the ancient bridge and the town’s most picturesque corner. In the golden hour, the lanterns reflected in the water, and the whole town seemed to hold its breath.

We had the fortune of being guided by Mr. Hara, a direct descendant of one of Kurashiki’s founding families. He led us through temples and tunnels, private villas, and into the Ohara Museum of Art, home to an unexpected collection of Western works, each piece a reminder of the city’s openness to global ideas even in earlier centuries. Walking the streets with him, the town came alive in a new way. Every tile, every scroll, every garden path was part of a larger narrative, one written not only in stone and ink, but in memory, effort, and preservation.

That evening, we gathered for our final dinner at Ryokan Kurashiki, a final gesture of hospitality that distilled the essence of all we had experienced. The menu unfolded like a ritual, each course a symbol, a memory, a note in the larger symphony of Setouchi. Kumquat aperitif, inarizushi wrapped in fried tofu, parrot fish broth, thinly sliced sashimi kissed by salt and citrus, warm radish carved in the shape of a masu cup, grilled Spanish mackerel and local beef shabu-shabu, each detail in harmony with the season, the place, and the philosophy of presence. Dessert, strawberry, apple, kumquat ice cream, was served in silence, broken only by a shared glance across the table. The kind of silence where no more words are needed.

A Final Ascent, and a Return to the Beginning

At sunrise, we climbed to Achi Shrine, high above hiki, where the town below still slept beneath a veil of morning mist. The shrine is a collection of buildings bound by reverence and time, where the sacred is not explained, only felt.

Ceremonial ropes tied to stones symbolize eternal love. Students leave wide-eyed ceramic vessels in gratitude. The wooden architecture is restrained, and all the more profound for its simplicity. The wisteria at the edge of the complex, known as Achi-no-Fuji, is believed to be among the oldest in Japan. Its twisted branches, long dormant, will bloom again when the season turns.

The view from the shrine opens across rooftops and gardens, canals and stone bridges, until it touches the farthest horizon of the Seto Inland Sea. There is no spectacle. No grandeur. Only the vastness of memory, and the gentle certainty that we had seen something rare. In that quiet, I thought again of the journey’s beginning, of fire and water, of ancient sailors, of a culture preserved through silence and care. And I understood that Setouchi, once hidden, is moving again.

Across the region, the sea welcomes the return of yachts. Throughout our trip, we found moorings ready, even at sacred ports like Miyajima. In Kurashiki, Onomichi, Mitarai, these towns, once formed by maritime trade, are opening their arms again. Yachting here is not disruptive; it is part of a very old conversation.

To understand the evolving landscape of Japanese yachting, I met with Kenta Inaba, CEO of SYL Japan Co. Ltd. With years of experience in the Fort Lauderdale superyacht scene and a quiet determination to connect Japan with the global yachting community, Mr. Inaba has worked tirelessly to open these shores. Today, regulations are favorable. Visiting yachts can move freely between major Pacific hubs and enter Japan without difficulty. The Seto Inland Sea, protected, scenic, and filled with cultural significance, is especially well-suited for extended cruising. A local agent is recommended, particularly for navigating customs and language, but the welcome is sincere, and the infrastructure discreetly capable.

Setouchi is no longer a hidden world. She is, instead, a revealed one. Still sacred, still serene, but willing now to be seen.

And as we descended from the shrine and made our way back through the quiet lanes of Kurashiki, we carried with us not souvenirs, but impressions. Echoes of archers in the hills of Hiroshima, of geishas’ laughter in forgotten port towns, of tea brewed with intention, and sails moving silently through the channel winds. Setouchi had not shown herself all at once, but in layers, tide by tide, temple by temple, course by course.

Slowly, quietly, she had become part of us.

Acknowledgments

This journey through Setouchi was made possible through the generosity, insight, and hospitality of many remarkable individuals and institutions. I am deeply grateful to the Setouchi Tourism Authority and Mr. Hiroshi Sakamoto for their gracious support and guidance throughout the region. My thanks to Mr. Kenta Inaba of SYL Japan Co., Ltd., whose expertise in Japanese yachting opened a clear course through these storied waters. Special appreciation to Mr. Hiroshi Maeshin of Nippon Travel Agency, whose deep knowledge and presence as our expert guide brought each destination to life with clarity and care.

To Mr. Tom Miyagawa Coulton, thank you for sharing the hidden stories of the Seto Inland Sea with such depth and honesty. To Genki Takahashi, whose tea ritual in the hills of Onomichi offered a rare and intimate window into Japanese tradition, your dedication turned a simple moment into lasting memory. In Kurashiki, our gratitude goes to our local guide from Takahashigawa Travel, whose perspective and storytelling helped us navigate the cultural heart of the town with ease and insight.

We also extend our warmest thanks to the hosts of Ryokan Onomichi Nishiyama and Ryokan Kurashiki, who redefined hospitality and gastronomy with every carefully prepared detail, and to Joycruise for providing a flawless experience aboard Ocean Point VII. To all those who welcomed us along the way, with quiet generosity, deep knowledge, and open hearts, thank you. This editorial exists because of your commitment to preserving and sharing the soul of Setouchi.

Photos: Ministry of Environment Japan, Ryokan Kurashiki, Tom Miyagawa, NAVIS Magazine - Words: Pablo Ferrero